Rolex. What springs to mind when you hear that word? Probably the image of a stainless-steel watch with a black dial and bezel. Maybe a yellow crown with a dark green background. Or perhaps a sense of quality of craftmanship, precision timekeeping, timeless excellence.

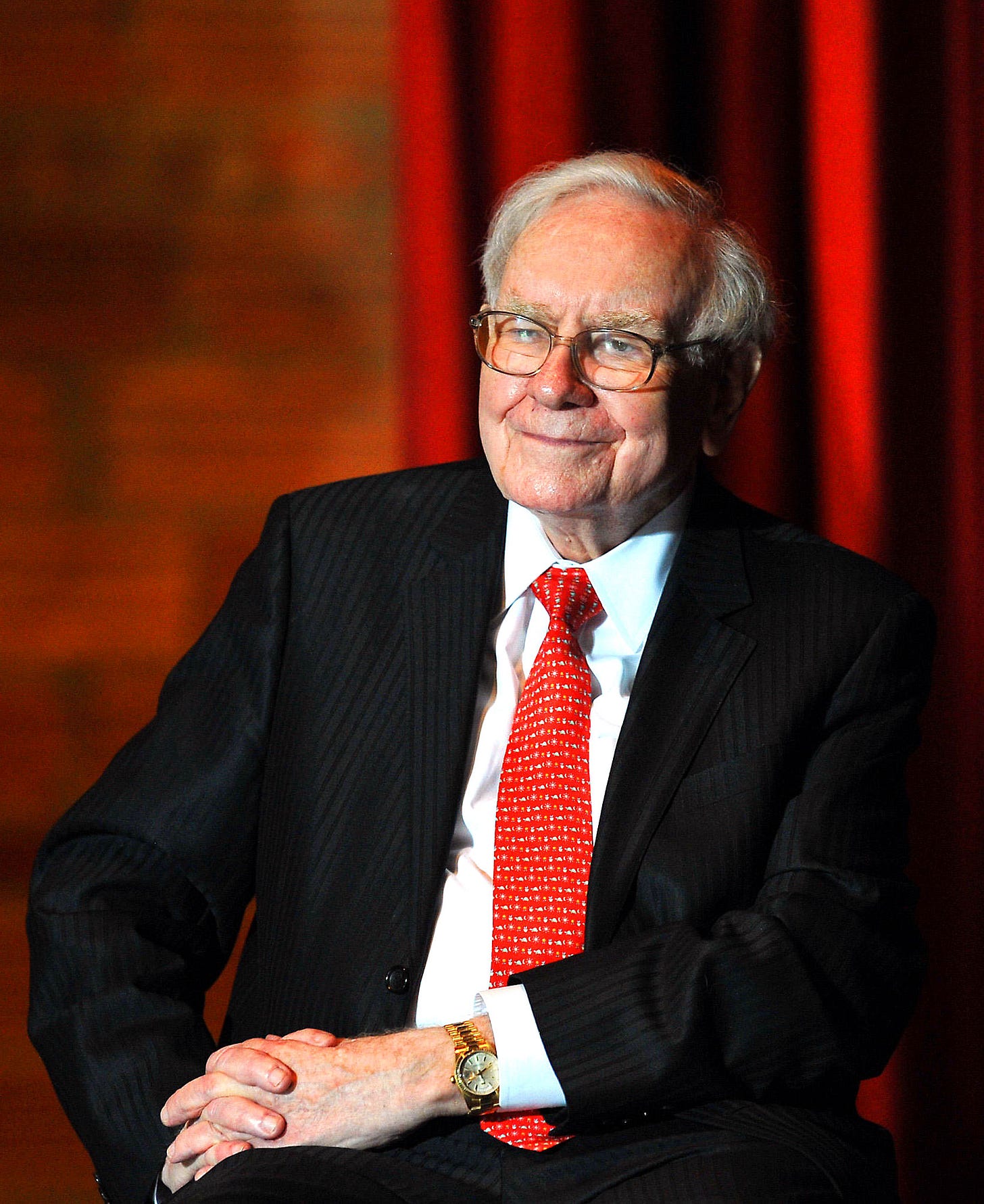

The best brands in the world have a mindshare of distinctive positive associations that come from decades of cultivating their image. This stems from making high-quality products, clever marketing, and methodical merchandising. This moat is intangible, and although it’s impossible to measure exactly, it’s incredibly valuable: it’s the biggest competitive advantage that many brands possess. Warren Buffett understood this when he invested in Coke, Lou Simpson when he invested in Nike, and Bernard Arnault as he built his LVMH luxury empire.

Luxury brands are not like regular brands though. They possess a different set of qualities and follow different rules, almost opposite to traditional business.

What makes Rolex Rolex? I think is a question worth exploring because it probably comes as close as anybody else to a globally recognized luxury brand. That is not a small feat. It’s neither intuitive nor obvious the amount of effort, time, sacrifice and thoughtful strategy it’s taken them to get to this level.

To analyze how they achieved this through first principles, we first must define exactly what we’re solving for.

What is a True Luxury brand?

Luxury has a very broad definition. It’s subjective, emotional, personal. Look no further than the replies to this Tweet, where I asked people: What are the most successful American luxury brands? The list was long: Tesla, Apple, Crocs, Nike, Patagonia, Coach. I should have been more careful in my choice of words, but I meant true luxury. I don’t think any of those brands fit the definition of true luxury.

Luxury is a spectrum. According to Brunello Cuccinelli, there are three types of luxury brands. If we imagine a pyramid, at the top is true or absolute luxury, in the middle is aspirational luxury, and the bottom accessible luxury. The top is where only the very best of breed sit and there are only a handful of them for any given category. Those that sit below can only dream of one day becoming part of that prestigious club. In the words of RH’s Gary Friedman, climbing the luxury mountain is incredibly hard, and has rarely been done. What separates the top from the bottom is having traced their own path for a very long period of time.

A true luxury brand has the following characteristics:

An obsession with high quality and craftmanship. It innovates and surprises, but always stays true to their core image.

It’s exclusive and scarce. Products are hard to get. Consumers make a deliberate effort to get their hands on them, not the other way around.

It evokes a certain status in the mind of consumers (both the buyer and the general public). This could be wealth, refined taste, appreciation of culture or history.

Rolex is worthy of study for various reasons. First, I have a personal bias towards watches. They’ve always fascinated me, maybe it has something to do with the engineer inside me or the aesthetics of a great looking watch. Second, Rolex is counterintuitively one of the best known brands in the world, and also one of the least known businesses. A lot has been written about luxury businesses, especially LVMH, but Rolex is extremely secretive and its business remains mostly a mystery. It's not a public company, quite the opposite in fact: it's owned by a foundation which operates as a non-profit. Third, it’s one of the very few companies I can think of that climbed the luxury mountain — and this was almost by accident.

Please consider subscribing to FinChat to support The Sleepwell Strategy and help keep the content free for everyone to enjoy. Sleepwell readers get a two-week free trial and 15% off paid-plans using the link below🙏

Climbing the Luxury Mountain: A Short History

Rolex was founded by Hans Wilsdorf and his brother-in-law in 19051 as Wilsdorf and Davis, specializing in making wristwatches in the UK. Three years later they came up with the Rolex name because it was short, easy to pronounce in any language and they thought it sounded similar to the sound of winding a watch.

The idea of going into wristwatches back then was controversial. At the time, pocket watches were the norm. People did not associate wristwatches with good timekeeping nor were they fashionable, and the most accurate watches in the world were pocket watches. Wilsdorf addressed this by certifying his wristwatches with the the Kew Observatory in the UK (which certified marine chronometers for the British Navy), thus making the first wristwatch to be awarded with this certificate.

After successfully proving he could produce precise wristwatches, Wilsdorf moved on to water resistance. He recognized that, unlike pocket watches, wristwatches were a perfect companion to be used in water sports. He devised a clever storytelling PR stunt to market this feature to consumers.

Mercedes Gleitze was famous for being the first person to successfully swim across the English Channel, so Wilsdorf asked her to wear a Rolex the next time she attempted it. This time she didn’t make it, after 10 hours in freezing water she couldn’t continue due to numbness of her extremities. But that didn’t matter. Wilsdorf ran a full-page ad showcasing that a Rolex watch withstood 10 hours in the freezing cold English Channel water while perfectly keeping time.

After successfully producing and marketing a waterproof wristwatch, Wilsdorf went on to make a watch that would power itself; what is known as an automatic or self-winding watch. For this Rolex invented the weighted rotor (using the wrist’s movement to accumulate elastic energy to power the watch), which effectively became the industry standard in watchmaking.

As years passed, the brand became more and more popular given their superior quality and timekeeping accuracy. They introduced two new models which would become so iconic in their design that almost every other watch brand copied it: the Datejust and the Submariner. The latter was the first “Professional” watch2, designed specifically for scuba diving, given its high depth ratings. Later on, Rolex would introduce other iconic models well-known to this day such as the Daytona (chronograph for car racing), GMT-Master (two time zones for pilots), and Sky Dweller (annual calendar for travelers).

At this point, Rolex didn't sit in the top of the luxury mountain. In the 1970s you could buy a Rolex for $200, or about $1000 in today’s dollars3. Some of them you could even fetch at a discount. Back then it was considered a high-end purchase, mostly justified by its high quality and precision. Also keep in mind there was no other way to keep time; these were considered high-tech instruments.

Then came the crisis. In the 1970s the Japanese brand SEIKO invented the first quartz watch, which was orders of magnitude more precise than mechanical watches, backed by a battery4. The entire Swiss watch industry almost got decimated as a result, given that their main competitive advantage and reputation relied on accurate timekeeping. A lot of brands disappeared during this time, as they couldn’t compete. Rolex instead, saw an opportunity. First, they developed their own quartz watches to compete with the Japanese, and second it shifted its product positioning to luxury by producing 18 karat gold watches and aggressively raising prices5.

How Rolex Represents True Luxury

Rolex lives and breathes the three attributes of a luxury brand like no other. To get a better understanding of what it takes to build this moat, let’s explore some of the strategies the company employs.

Quality: The Perpetual Pursuit of Excellence

It’s an understatement to say that Rolex has an obsession with quality. This goes back to the early days of Hans Wilsdorf. The three manufacturing tenets that he implemented 100 years ago (precision, waterproof, self-winding) are still at their core today. Here are a few examples of the processes that take place in their watch making.

Rolex uses only the best materials in the world. Not only that, but they went as far as building their own foundry. Here they make their own patented metal alloys and precious metals, including three types of gold and their famous 904L stainless steel, which is aerospace grade level of durability. They have a laboratory filled with world-class experts in materials engineering, friction, lubrication, wear, chemistry and physics. Oh, and Rolex employs two Nobel Prize winners in their team.

Rolex quality control goes to an extreme. They are fully vertically integrated, making all their components in-house and put to the highest standards. Their waterproof test places watches into pressurized tanks that simulate the guaranteed depth rating of every model with an additional 10% margin for regular watches and 25% for dive watches. The 24-hour accuracy test photographs watches and exactly 24 hours later it’s photographed again, if the images are not microscopically aligned, they’re sent back for revision. They invented a machine that opens and closes the bracelet clasp 1000 times per minute. The finishing phase, which includes polishing of the case, is done 100% by hand. They have a proprietary machine that tests diamonds and stones to make sure they’re up to their standard and aren’t fake6. They also have machines to test their own machines. Is that obsessive enough?

Rolex consistently pushes the boundaries of innovation. After making a pretty good dive watch with the introduction of the Submariner in 1953, Rolex didn’t stop. An average scuba diver rarely goes below 100 feet, while the first Submariner was good for 300 feet (100 meters) of depth. Rolex doubled, then tripled the depth rating in the subsequent models.

In the 1960’s they partnered with the U.S. Navy and the French exploration company COMEX, to develop professional watches exclusively for deep-sea exploration. But they ran into a problem. To reach extreme depths, divers spend days in an underwater chamber that is pressurized using a mixture of oxygen and helium for breathing7. Helium, for those that flunked chemistry class, is the smallest element in the periodic table. This meant that the gas was able to enter the watch through the edge between the crystal and the bezel. During the decompression stage8 as the divers ascended back, the outside pressure decreased and the high pressure helium inside the watch made the crystal pop off like a champagne cork.

While other watchmakers struggled to solve this, Rolex devised a simple solution: create a unidirectional valve that would operate only when the pressure outside was lower than inside the chamber, thus the helium gas could automatically escape during the decompression stage. They called it the Helium Escape Valve.

Things didn’t stop there though. Rolex kept pushing the depth rating, quite literally to the limit. The Deepsea Challenge was introduced last year and has a maximum depth rating of 36,090 feet (11,000 meters), or equivalent to the deepest point in the ocean, the Mariana Trench. To put into perspective the pressure at these depths, it's 16,000 pounds per square inch or 1000X the atmospheric pressure at sea-level. In fact, the watch accompanied James Cameron on his expedition there, hanging right outside the submarine9. There’s literally nowhere deeper you could take the watch (at least on this planet).

The result of this obsession with quality is a simple yet powerful promise that consumers can trust: anyone buying a Rolex knows that the watch will be working perfectly fine decades from now, when they decide to pass it on to their child.

Exclusivity and Scarcity: The Waitlist

I have a challenge for you. Go into any Rolex boutique, ask if they have any watches available for purchase and I think you’ll be both surprised and out of luck. Pretty much all their products are out of stock. You’ll have to join a mythical “waitlist”10, as you explain to the Sales Associate why you’re worthy of owning a Rolex.

Think about this for a second. The roles have reversed: instead of a salesperson chasing you down and trying to convince you to buy something, you have to be the one convincing them to sell it to you!

It wasn’t always like this. There were always a few models in high demand that were hard to get, like the Daytona. But today it’s totally different. On the supply side, it’s mostly an outcome of the strategy employed by the Rolex CEO known as shrink to grow, where Rolex reduced and optimized its retail footprint while production has only increased somewhat. Rolex also periodically will discontinue certain models, making them even more desirable in the aftermarket.

More importantly, the demand has far outstripped the supply (which includes both new and used models). This is testament to the Rolex marketing strategy, as well as a general increase in public interest for high-end watches over the last few years.

One of the most basic rules of luxury is that you always sell less than what is demanded. The book The Luxury Strategy explains it nicely:

“A luxury brand must have far more people who know it and dream it than people who buy it.”

This is a very simple concept, but incredibly hard to follow with discipline. What makes it so hard is the natural desire for companies to chase growth (exacerbated if you’re public), which in the short term would cause a quick spike in sales, but in the long term can impair the value of the brand. It’s also why investing in marketing and advertising is so important, no matter the circumstances. Rolex was quite aggressive in stepping up marketing investments during the Great Financial Crisis, while others were pulling back. They have always worked with the same advertising agency achieving consistency and effectively delivering a clear message.

The outcome of this strategy is also reflected in the value of secondary market prices for most Rolex watches, which typically trade above retail value — sometimes as high as 100%.

Making this even more impressive is the fact that Rolex sells over 1 million units per year, at an average $13,000 per watch. For context, the legendary Birkin and Kelly handbags from Hermès sell about 1/10 the number of units at similar price points. There’s really not anybody else selling those kind of volumes at those price points in Luxury, which is mind-blowing.

Status: The Promise of Timelessness

Status in luxury is typically associated with money. But buying a Rolex (or any watch for that matter) isn’t necessarily about the “flex” of showing it off. There are many legitimate reasons why one would buy a Rolex: to celebrate the birth of your newborn, a fascination with the craft of watchmaking, the design aesthetics, the history it represents, a potential investment. Maybe you’re into scuba-diving so you want a Submariner. Or you love racecars so you want a Daytona. These pieces carry a lot of sentimental value for people, and to many it’s more like a piece of fine art.

Rolex has spent decades cultivating their image and reputation. They are very selective with who they partner with and always strive to be associated with excellence, in both performance and character.

Rolex’s partnership with golf began in 1967 with Arnold Palmer, and was soon followed by Jack Nicklaus (still to this day a Rolex ambassador). The company’s commitment to the sport has been persistent, sponsoring the major tournaments and best players. In tennis, their sponsorship began over 40 years ago and their relationship with Roger Federer goes back to 2001.

Rolex also tailors their products to a very important set of customers: collectors. They do this by creating limited edition pieces, off-catalog pieces, discontinuing some models, and paying homage to historical pieces, such as an anniversary piece that celebrates the original model with a twist.

Collectors are the biggest supporters and marketers of the brand, and high-profile auctions make for excellent PR for Rolex. These are only possible given the heritage and history behind the models. For example, in 2017 one of Paul Newman’s watches (a Daytona) famously sold for $18 million, which brought even more popularity to the entire Daytona model lineup. A brand that hasn’t been relevant as long as Rolex and has no heritage simply cannot replicate this.

The Rolex design ethos is such that it always stays true to their original design code, while simultaneously making slight adjustments and improvements (sometimes without telling anyone). It’s this strategy that assures that it never goes out of style. You can be pretty sure that if you buy a watch today, it will still look quite fashionable decades from now.

That said, predictability is not always the name of the game. Every now and then they do something completely unexpected. Recently, they announced a watch with a jigsaw puzzle on the dial, emojis instead of the date and words of affirmation instead of the day. Notably, this model is called the Day-Date, and neither are featured on this specific model. Needless to say, it was quite controversial and created a ton of buzz.

How much is Rolex Worth?

It’s an interesting thought experiment to think how much Rolex would go for if it were a public company. Let’s look at some numbers.11

According to Morgan Stanley, Rolex has a ~30% market share in the Swiss Luxury watch market, which is more than the next five competitors combined12.

Rolex sells roughly 1.2 million units per year, at an average wholesale value of $8,050 plus some other revenue items (like servicing, repairs and parts) we arrive at somewhere between $10-11+ billion of revenue per year.

It’s fair to assume that Rolex has a 30-40% operating margin. This is higher than both LVMH’s Jewelry and Watches Group and Richemont’s Specialty Watchmaker’s Segment (both ~20%) since their watch portfolio skew to smaller, less exclusive brands (on average). The majority of the profit pool sits in the Top 5, which gives Rolex much higher margins (not to mention their immense scale). Also recall that Rolex is fully integrated, which saves on costs.

If we apply an Hermès /LVMH/Ferrari like historical multiple of 30-40X on earnings13, this means Rolex is conservatively worth more than $100 billion. I think 20X would be a steal for a company of this caliber and would rarely trade in that zip code. And if it were public today, looking at current multiples, would probably be worth twice that amount.

Too bad you can’t invest in the company, and I would argue there’s really no comparable publicly traded company out there14. It's not for sale either, rumor says Buffett even tried to buy it once and failed!

What about buying an actual Rolex? I think there’s probably some decent correlation, but you’re likely to vastly underperform the intrinsic value of the underlying business, which spits of insane amounts of cash and requires little capital to grow. I think at the very least the performance of their watches should keep up with inflation, while certain pieces could trade more like coveted pieces of art.

There’s some interesting stories of people who’ve done pretty well investing in watches. My dad actually bought a Rolex GMT Master in 196715, right out of High School, for about $200. That watch is worth about $20-30,000 today or about a 9% annualized return over 56 years. Certainly not bad!

Closing Thoughts: What’s Next for Rolex?

A few predictions for how the next few decades at Rolex will look like (spoiler: more of the same).

It will stay private and owned by the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation.

Its model lineup will look very similar. Yes there will be a few surprises, tweaks, and improvements along the way, but aesthetically it won’t change much.

Like clockwork (pun intended) it will exert its pricing power and raise prices ~6% per year. Production will also increase, but always less than the demand.

The only part of the value chain that they don’t control is the selling. I think Rolex could eventually take their retail distribution in-house and go full DTC. This would let them keep more control of the inventory, demand, the selling experience and who their customers are.

Acknowledgements:

This writeup would have been impossible without the work of a few watch experts. I want to especially thank Ben Clymer at Hodinkee, who’s written extensively about Rolex and was featured in an excellent Business Breakdowns podcast. This piece borrowed a lot of information from his work. The Luxury Strategy is a great book to understand how Luxury works and strategies employed. Also my friend Eric Boroian, has taught me a lot about how to think about Luxury generally. Finally, Jose Pereztroika of Perezscope is probably the person who best knows the history behind the Sea-Dweller.

Interesting Sources for Further Reading/Listening:

Perezscope — History of the Sea-Dweller

Talking Watches with John Mayer: Part I and II (if you want to see a real watch collector)

Other Sources:

Morgan Stanley Annual Swiss Watcher Report

Rolex Website

Bob’s Watches

The Rolex Magazine

This is not that long ago in the context of luxury brands with a long heritage: Hermès was founded in 1837, Vacheron Constantin (another watch brand) in 1755.

Years later this category came to be known as a sports-watch, given it could be worn casually everyday (instead of just for special occasions).

By contrast, the average Rolex today costs upwards of $10,000, going up to 6 figures for some exclusive models.

Originally it was quite expensive, but eventually became much cheaper than mechanical watches.

This is why in the 80’s gold watches became so popular.

Only about 1 in 10 million actually fail the test.

Oxygen is toxic at high pressures.

Scuba divers need to spend a certain amount of time during ascent at different depths for safety reasons, to avoid something called The Bends.

Quite fascinating that they used the same tactic as 100 years ago when Mercedes Gleitze swam the English Channel with a waterproof Rolex hanging by her neck.

There’s actually no such thing, the Sales Associate will allocate availability based on purchase history, relationship and who’s buying it (being famous helps).

None of this is public and mostly relies on 3rd party estimates. Rolex doesn’t disclose anything.

Omega, Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet, Cartier, Richard Mille.

This is where these true luxury companies have traded historically; more recently the multiple is much higher. Just trying to be somewhat conservative.

Closest brands are Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet, both of which are private as well. Swatch Group owns Omega, which would certainly be interesting if it where to be spunoff.

Refence number 1675, also known as the Pepsi

Loved this. I am the proud guardian of three “Rolexes of the dead,” a Submariner red inherited from my husband that I gifted him in 1974, a Daytona inherited from my best friend, and a Datejust inherited from my oldest friend. None of them will ever be for sale.

One guy I knew never set his Rolex to the correct time. Strictly ornamental...