Music Streaming Royalties 101

Understanding the value chain through the life of a song and following the money trail

This post is brought to you by FinChat. Please consider subscribing to support The Sleepwell Strategy and help keep the content free for everyone to enjoy. Sleepwell readers get a two-week free trial and 15% off paid-plans using the link below.

“Music royalties are a complicated subject” might be the mother of all understatements. In this piece I will try to cover the basics of streaming royalties in the U.S., by walking through the process of creating a song, producing it, distributing it and monetizing it. Each of these steps are important to understand who the players are. My goal is to give you a decent understanding of what royalties are, how they work, where the money flows and demystify misconceptions; all while trying to not make you fall asleep. A daunting task indeed.

What I’ve learned comes from having studied the industry closely in the past few years and recently getting more involved by investing and working with a few artists as well as beginning my own journey as one.

Let’s begin.

Why are Songs so Complex?

The complexities of the music industry stem from two places:

First, the amount of intermediaries that are involved in the creation, production, distribution and monetization of a song (who therefore need to get paid): songwriters, artists, producers, musicians, labels, publishers, distributors, managers, agents, lawyers, streaming platforms, digital stores, radio, collection societies and the list goes on.

Second, the way music copyright law has evolved and the sloth speed at which it adjusts to changes. Laws are static in nature and not meant to keep up with the fast pace of technology and music consumption habits. For example specific laws that made sense for the sale of CDs make absolutely no sense for streaming a song over the Internet.

The following is the most important and basic definition of this piece ⚠️

Legally speaking, a song is made up of two separate individual copyrights:

1) The Composition: the notes, melody and lyrics as they would be written down on a musical sheet. It’s the song in its most stripped down form. Think of this as the equivalent of a movie script describing the scenes and dialogue.

2) The Sound Recording (or Master): the actual musical recording that gets released to the world and played in all the mediums such as streaming platforms, digital stores, vinyls and the radio. Think of this like the final cut of a movie that is shown in a movie theater and Netflix.

Each one of these halves have different intricacies, laws that protect them and monetize differently. This is also why they are considered two different and separate businesses, known as Publishing and Recorded Music. For example, a concert pays a publishing royalty, but not a recorded music royalty because the artist is interpreting a version of the song, making use of the composition, but not using the literal sound recording that came out of the studio.

Music Publishing derives its name from the historical act of publishing musical scores and nowadays refers to Publishers, which are companies that work with songwriters to pitch songs to artists (who will perform and record them), monetize them, and collect the earnings which are split evenly between the publisher and the songwriter.

Recorded Music is more commonly associated with Music Labels1. Labels oversee the production of an album, promotion, distribution and monetization of the Master. The Label typically owns the Master (given the financial risk they take) and pays a portion of the earnings to the artist who signed a record agreement.

A Song is Born: Composing, Recording and Distributing

Taylor is a fictional artist who wrote a song called Sleepy Love. Recently heartbroken, she got inspired, found a beautiful chord progression in the guitar and wrote lyrics on top of them. She recorded a voice note and excited, starts to think about how to put it out for the world to hear. The composition of the song has been created and as the sole songwriter, Taylor owns all the rights to the composition of Sleepy Love. Riding the wave of inspiration, Taylor goes on to write another nine songs.

She now has two options:

She can be a performer, meaning she will go into the studio to perform and record these songs. She will be the artist which everyone associates the songs with.

She can focus on being solely a songwriter by pitching the songs to other artists who will perform them and record them. In this case, she will stay off the grid as the songs will be interpreted by someone else.

It becomes clear here that the songwriter and the performer can be two separate entities (thus make money separately) and in fact many artists are really performers and don’t write their own songs. That includes The Weeknd, Justin Bieber, Britney Spears and The Backstreet Boys, who have an army of songwriters that write on their behalf. For example, checkout Max Martin’s resume, a Swedish songwriter you’ve heard thousands of times but never realized it (told you they’re off the grid).

Taylor wants to be a superstar so decides to take the performer route. Now she needs to find a producer, a person who specializes in recording albums — think of an album producer as the equivalent of a director in a movie. The producer will help her conceptualize the album, pick songs and musicians and transform it from a voice note to a professionally recorded song full of instruments, beats, arrangements, samples to make sure the final product sounds awesome.

Mark is a Producer in “Begin Again” — He Imagines The Final Song

The problem is a producer costs money, and so does renting out studio time, paying sound engineers and hiring a drummer and a bass player. If Taylor has the money, she could pursue an independent path, if not she needs to find someone to finance and promote the album. Guess who has money, know-how and the right connections? That’s right, a Label.

Luckily, Taylor’s uncle is an A&R in Warner Music Group (A&R’s find and develop talent), so he signs her to the Label on a record contract that looks (simplistically) like this:

Taylor will get a $50K advance (aka loan) to be used for album production costs, promotional videos and living expenses.

The label in exchange will use the future earnings of the album to recoup the advance (repay the loan) and after fully recouping it, will split the earnings 85% for the Label and 15% for Taylor, in return for financing the album.

Because they financed the album and took a risk with an unproven work and artist, the Label will own the rights to the Master Recording while Taylor will receive a cut from the earnings it generates2.

The contract will last for 5 years, meaning Taylor is obligated to work exclusively with the label on songs released during that time, after which she can look for another label (or go independent) to release new songs, but the Label will still own the songs recorded during the contract (and pay Taylor her share).

Taylor signs the deal, records all the songs in the studio and the album gets distributed to all the Digital Service Providers (DSPs are streaming platforms and digital stores like Spotify, iTunes and even TikTok) to start being monetized. The label will also market and promote the songs, through radio and playlist placement, PR, advertising, music videos, artwork and working on the artist’s image.

Alternatively, if Taylor had the money to finance the album, she could have gone the Independent route (indie) where she would record it herself, skip the label and work instead with a distributor (CDBaby, TuneCore) who takes care of distributing her work to all the DSPs. Distributors exist because it would be impossible for Taylor to upload her songs separately to all the different places (artists want maximum exposure)3 and then have the added complication of having to collect royalties from each one.

All independent artists work with a distributor while signed artists work with a label who either has their own internal distributor or works with a third-party distributor. In essence, Independent artists take two of the label’s roles into their own hands — recording and promotion — while outsourcing the third, distribution. This is only possible in the Age of the Internet: home studios are easy to setup given cheap software and hardware, promotion can be done through social media and distribution used to mean manufacturing and selling CDs instead of uploading digital songs.

A Song is Streamed: Time to Monetize

The following example applies to streaming platforms, more formally known as interactive (or on-demand) streaming, since users can pick any song to play as long as they pay a subscription (or listen to ads in the case of Spotify). Streaming platforms’ agreements with Labels, Distributors and Collection Societies are highly complex and confidential, but transparency around broad numbers has increased recently to create more awareness for creators. Generally, platforms pay ~2/3 of their revenues to rights-holders4. This payout is split between recorded music and publishing (remember: two different businesses). The royalties are calculated based on a stream-count share, or how much each rights-holder’s songs proportionally accounted for the total number of streams in a specific period of time at a certain jurisdiction. Best to go through an actual example.

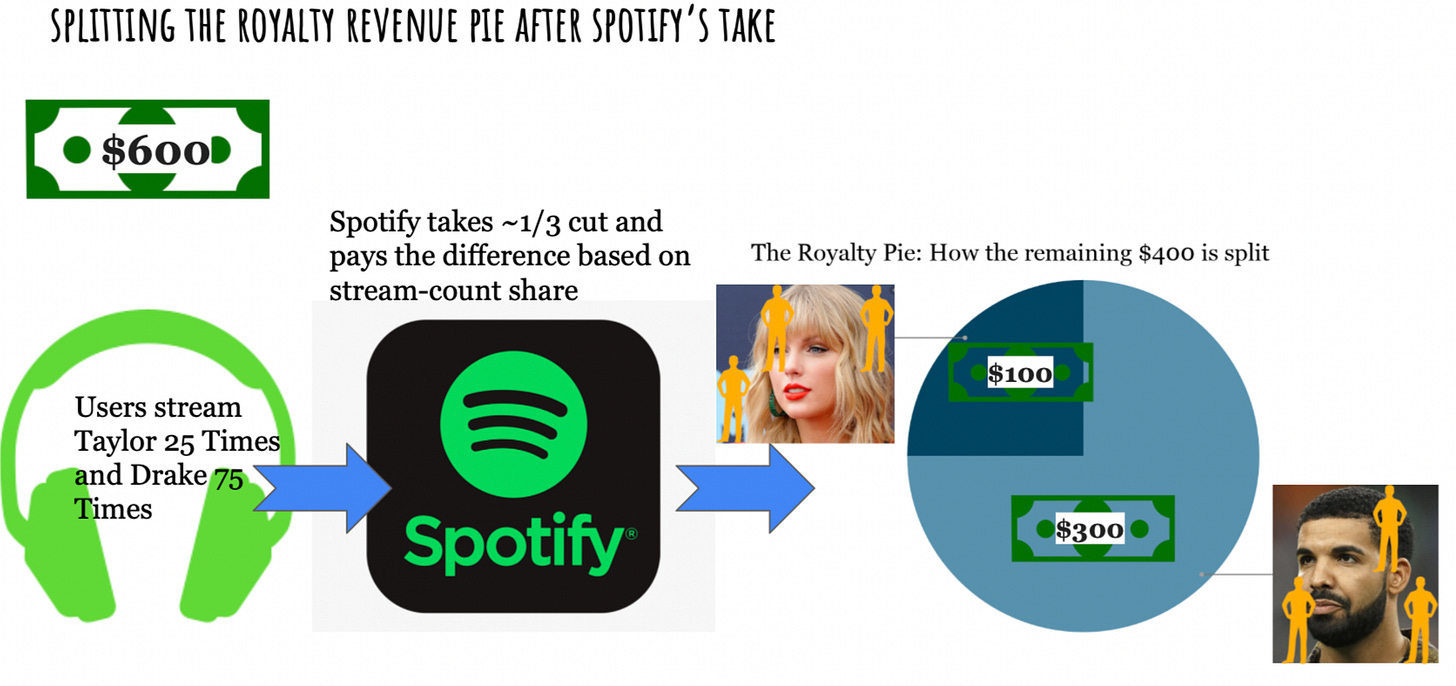

Let’s say Spotify has 60 users in the country of Sleepyland and each user pays $10 a month for a total of $600 monthly revenue. Sleepylanders only listen to two artists: Drake and Taylor. During the month of April, users streamed Drake’s songs 75 times and Taylor’s songs 25 times for a total of 100 streams.

From the total revenue pie of $600 for the month, Spotify will take a cut of ~$200 and the other ~$400 will be distributed to rights-holders in accordance with the stream-count share calculation. Drake’s songs will receive $300 (75%) and Taylor’s songs will receive $100 (25%). Notice that I said their songs, meaning Spotify doesn’t pay artists directly (a huge misconception) but rather the intermediaries which are labels, distributors and collection societies. These intermediaries will take their cut and then distribute the money further down the funnel to artists, songwriters and other parties involved according to the contracts they signed.

Now let’s discuss the specific royalties that have to be paid out of Taylor’s royalty pool ($100 in the above chart) for each half of a song: The Composition and The Master (Sound Recording). Each part is treated differently and streaming platforms have different payout schemes for each. The Master is negotiated with and paid to the Labels and Distributors directly, while Music Publishing rates are overseen by the government and paid to collection societies. To complicate things further (ugh sorry), the Publishing royalty is split into two types: Performance and Mechanical, both are paid by streaming platforms to be able to use the Composition.

Performance Royalties are paid when music is played (performed) in public places, such as a Walmart, nightclub or a concert. This applies to streaming also since it’s considered a public performance (someone can play Spotify in a bar). Performance royalties are collected by a PRO (Performance Rights Organization) like BMI or ASCAP and these rates come from blanket licenses that determine the rate that is paid by the DSPs to the PROs and covers all of the works (instead of having to negotiate each individually). The rates are overseen by two judges assigned by the Department of Justice to prevent any antitrust behavior.

Mechanical Royalties relate to the sale of music that’s reproduced through a physical medium such as CDs. The name is historical (and thus confusing), referring to how Piano Rolls would mechanically reproduce music, and now also applies to streaming even though you don’t technically own the song (told you these laws were outdated). It’s a compulsory rate set by a government body called the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB) meaning anyone can use the works as long as they pay the required rate. Royalties are collected by a collection society, typically Harry Fox Agency or the Mechanical Licensing Collective.

The total payout for both performance and mechanical royalties (together Publishing royalties) is around 20% of the royalty pool (again, that’s after Spotify’s take) roughly evenly split for each royalty5. This royalty is paid out to the collection societies, which then subtract their overhead and then pay the Music Publisher’s who works with songwriters and typically splits the earnings evenly. Using the above example, Taylor gets $9 from publishing royalties (performance plus mechanical). She also wrote the song on her own, in the case where many songwriters are involved, this gets divided even further.

For Recorded Music, the use of the Master (Sound Recording) is what is negotiated between the DSPs and the Labels and Distributors. This is what gets most of the media attention (known as the Label agreements) and as opposed to the Music Publishing agreements which are overseen by the government, these are set by the free market thus go through lengthy, complex negotiations.

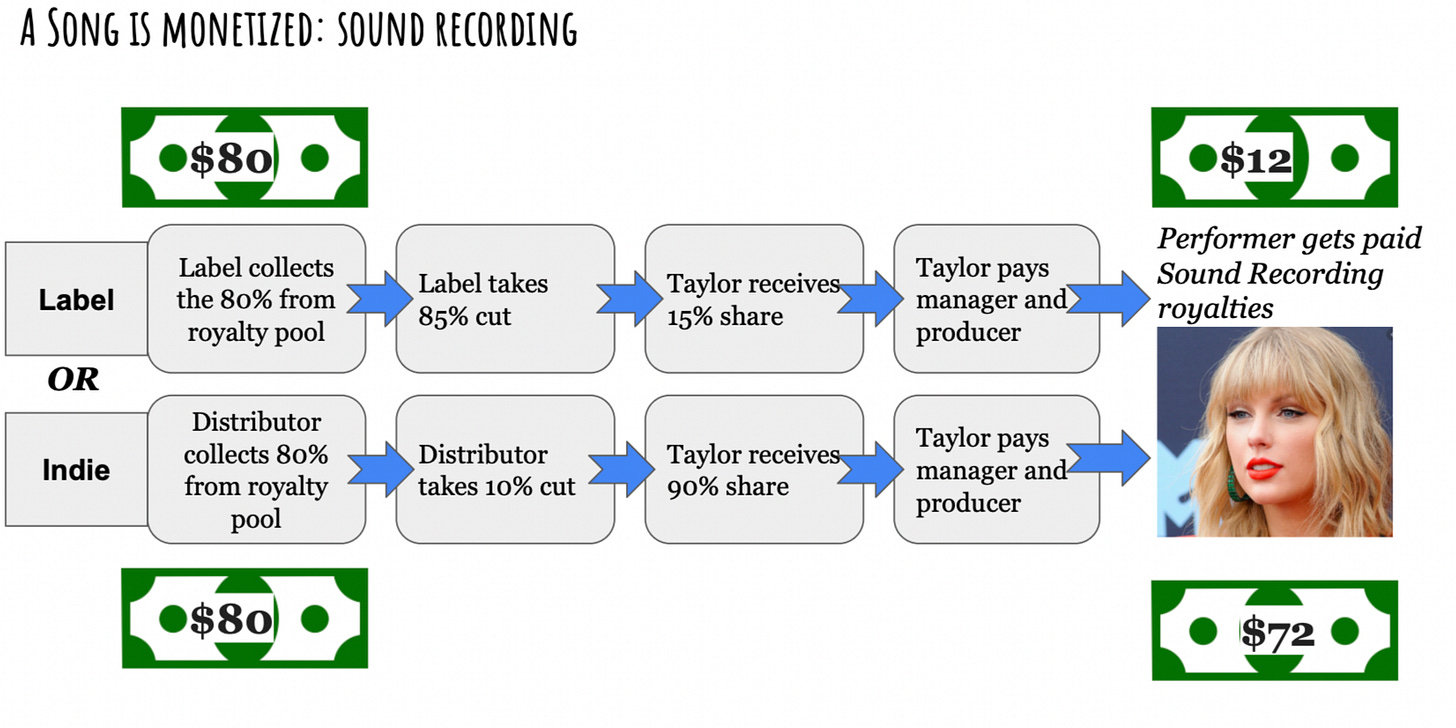

On the Master side, the labels receive a rate which is around 80% of the royalty pool. After the label gets its share, it is then distributed to all parties that were involved in the sound recording (performers and producers mainly). In Taylor’s case, the Label will take their 85% and pay her the remaining 15%6 resulting in $12 for her. An independent artist, will instead get the Master’s royalties after the distributor’s cut which is typically around 10% (in some cases as high as 25% depending on services offered) and receive $72.

Tying the Blurred Lines Together

When we look at the entire picture7, three things standout: First, labels are taking an outsized bite off the pie (45%); second, Indie Taylor makes a lot more money than Label Taylor (almost 4X) and third, there’s too many people eating from this cake (many not shown for simplicity). What does this mean for the future of the industry?

Labels are still a powerful force in the industry given their capabilities, connections, know-how and ability to invest in and grow their artists. It is unlikely that an equivalent indie artist achieves the same global reach as a signed artist unless they have the combination of talent, substantial capital, the right connections, a professional team behind them (manager, PR, agent) and powerful promotion and marketing tools. Nevertheless, it’s gotten easier to pursue this route and likely will continue to in the coming years. There are companies offering the roles and tools that traditionally labels would do (e.g. some distributors offer promotion) and the lines between players are certainly blurring. Importantly, the power is slowly shifting away from the intermediaries and towards the creators that make the content and platforms that own the demand. This likely means there will be more and better ways to monetize fans while not having to pay as much to the middleman.

One thing is certain: there has never been a better time to be an independent artist and the best is yet to come.

Although the Big Three Labels have their own Publishing arms as well

A discussion of whether this is fair is out of scope. Labels lose money on most record deals, so they need to make up for it with big winners (similar to a VC), but also their role and value add has diminished over the years

There are over 150 DSPs

These numbers are just an approximation and will vary greatly by jurisdiction as well as depending on a number of factors. The agreements are based on complex formulas with minimum guarantees, advances, marketing spend embedded, if and ors, and all sorts of different clauses. It’s not a just a simple percentage

Another approximation, can vary greatly. Again, not based on a straightforward percentage but a huge complicated formula

Assuming no other parties involved and that she has recouped the advance in full

Remember! this a hypothetical example and not in any way a one size fits all. Every artist’s situation is unique and different in terms of agreements that are in place and parties involved.

Marvelous article, thank you! Coming from Eagle Point Cap.

Hi Sleepwell, a thousand thanks for writing this. Someone posted a link to this under the PSTH subreddit and I'm so glad I caught it. This is very informative. I have a couple questions I would love to get your thoughts on, if you don't mind me asking.

Very broadly, what are your thoughts on Universal Music Group as an investment?

I was originally sold on the strong IP that UMG has, and more importantly their "know-how" of making a star. While it continuously gets easier to publish music online, the fact that this is a benefit to everyone results in it not being a benefit. In fact, that led me to the belief that UMG's ability to "make a star" by knowing how to promote/market is what upholds their importance and future success - their "moat". But with the advent of new technologies, such as Spotify, I am starting to wonder how defendable this "moat" really is. Thanks to technology, middlemen in any industry are increasingly being cut out, much like you alluded to, and I don't see how music is an exception. The Discovery feature that you mentioned even seems to be the beginning of exactly this. As Spotify is the platform that the users interact with, don't they have the power to one day choose which songs to promote? Thereby replacing what I had originally thought to be UMG's greatest asset - their knowledge of effective promotion?

From the other posts I've made asking for other's opinion on this I've gotten some counter arguments that UMG does a lot more than that and therefore will always be relevant. I don't completely disagree with that, but as an investment, I have to consider their future relative to today at the price I'm paying for today. In addition, I don't see the other services they provide as very defendable. Financing, for example, can very easily be Spotify's next path at vertically integrating itself within the industry.

I apologize for the length post, but would really like to hear your thoughts. Thanks!